This reflection is about a belief many Africans have carried for generations: the conviction that somewhere in our bloodline lies an extraordinary force like mystical, physical, or ancestral power that should naturally place us at an advantage in moments of crisis, conflict, or competition. If this power were as absolute as we were raised to believe, then Africa ought to dominate not only its own destiny but global arenas in events like sports, creativity, warfare, resilience, and the ability to confront hardship with a kind of supernatural ease.

For centuries, especially in Nigeria, we were fed stories coated with enchantment and awe. Tales of warriors whose skins repelled metal, kings who commanded lightning, hunters who vanished into thin air, and fighters who struck enemies with invisible forces. These stories shaped our worldview long before we encountered Western education, and they echoed the words of Mircea Eliade, who noted that societies often “sacralize power” when faced with forces they cannot fully understand. Our folklore taught us that charm-filled gourds, incantations whispered at dawn, or the secret consecration of amulets could turn ordinary men into legends. And history, particularly the confrontations with early colonial forces, was narrated to us through the lens of bravery amplified by supernatural backing.

The story of Etsu Abubakar of Bida, the Great, stands tall among these narratives. His resistance against the British was not merely a military encounter but a symbolic clash between indigenous courage and foreign technology. Historical records portray him as a brilliant strategist who rallied his people with spears, arrows, and a handful of firearms, all while invoking spiritual fortification. His leadership embodied the fusion of physical strength and metaphysical assurance. Yet even with all the fierce resistance mounted, the Nupe kingdom eventually succumbed to the relentless efficiency of British firepower. The fall of Nupe, along with the defeat of other formidable leaders like Sultan Attahiru I, Queen Amina, and Sarki Jatau, reveals an uncomfortable truth: courage alone, even with spiritual backing, could not outmatch the ruthless precision of industrial technology.

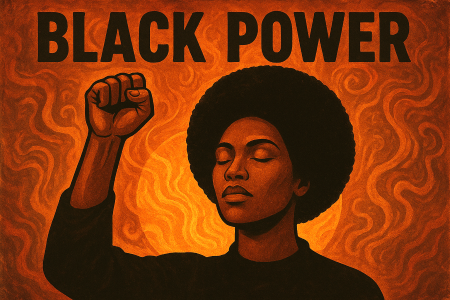

Still, these stories of supernatural valor refused to die. They seeped into our homes, our childhood games, our expectations about love, success, and even intelligence. I remember growing up in a world where almost nothing was believed to happen naturally. Excellence in school? It must be a charm. Winning a girl’s heart? Surely a potion was involved. Protection from thieves? One powerful talisman could trap criminals inside a compound, forcing them to sweep the yard until dawn. Business success? A secret ritual. Wealth? A sacred pot or a midnight invocation. The everyday became magical, and magic became the explanation for anything extraordinary. In many ways, the idea of “black power” became our informal technology, our mysterious substitute for the science we did not build.

Yet the test of any belief system is not in its stories but in its outcomes. And today, in the age of banditry, terrorism, mass abductions, and sophisticated criminal networks, the silence of this supposed power is deafening. If black power is real, where was it when entire communities were overrun by bandits? Where was it when children from St. Mary’s Catholic Church or schools in Kebbi vanished without a trace? One would think that among all the acclaimed seers, diviners, mystics, and traditionalists, someone should be able to pinpoint the exact location of abducted victims. But the charm-wielders have offered no guidance. Their silence has become a metaphor for a failing worldview.

The irony grows sharper when we turn to sports, the global stage where raw physicality, stamina, and strength seem closest to the traditional definition of power. Across football, tennis, Formula 1, rugby, cricket, and even athletics, Africa has dazzled but rarely dominated. Nigeria, with all its talk of spiritual strength and natural energy, has not conquered the FIFA World Cup, nor have African nations achieved supremacy in tennis Grand Slams, F1 championships, or cricket and rugby world contests. This is not for lack of talent; scholars point instead to structural and institutional limitations: inadequate infrastructure, inconsistent development programs, weak investments, and fragmented governance. Power, it seems, is not a gift; it is a product of systems, discipline, and long-term planning.

Boxing, perhaps more than any other sport, challenges our assumptions most brutally. I once believed that a Black man should naturally rule the boxing world, since it is a sport stripped to the bone—no weapons, no external tools, nothing but muscle, mind, and willpower. But even here, Africa has not dominated. Great boxers exist, yes, but the continent does not reign. As the sociologist Pierre Bourdieu observed, “physical capital” only becomes power when shaped by training, structure, and social investment. Raw energy is not enough, and charms do not win championships.

Meanwhile, claims about people being invulnerable to blades or bullets continue to circulate, yet none of these gifted individuals have stepped forward to defend their villages during attacks. No charm has shielded traditional rulers from deposition, as seen in the fall of Emir Sanusi in Kano or Etsu Usman in Bida. The guardians of mystical power have become victims of the same vulnerabilities that haunt everyone else.

Perhaps the most tragic failing of the black-power myth lies in medicine. If charms and herbal potency were truly superior, Nigeria would be a global center of healing, a pilgrimage ground for the world’s sick. Instead, even our herbalists turn to orthodox hospitals when illness grows severe. And while charms inspire the confidence of criminals and bandits by encouraging them with illusions of invincibility, they do little to protect them from bullets, arrest, or death. What they do succeed in is sustaining crime, delusion, and a false sense of immunity that endangers society.

The belief in black power has not only failed to save us; it has distracted us. It has slowed our embrace of science and weakened our investment in technology. It has given courage to criminals but offered no shield to innocent citizens. It has entertained us with beautiful stories but abandoned us in our most critical moments.

It is heartbreaking that a people so rich in imagination and heritage have been left vulnerable because the powers they trusted most have remained silent when their survival depended on them. Black power, as inherited from our myths, may still inspire awe, but until it proves itself where it matters, in protection, innovation, development, and global achievement, it remains a poetic illusion, cherished in memory but powerless in reality.

Bagudu can be reached at bagudumohammed15197@gmail.com or on 0703 494 3575.