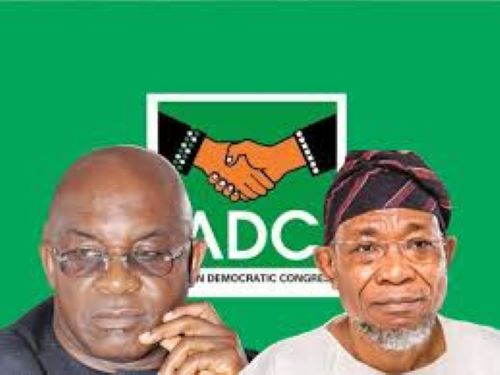

As Nigeria approaches the 2027 general elections, the political terrain is teeming with intrigue, maneuvering, and unexpected alliances. The recent announcement by leaders of a rebel faction of the Peoples Democratic Party (PDP) to join the African Democratic Congress (ADC) in a bid to unseat President Bola Ahmed Tinubu has sparked intense debate among political analysts and citizens alike. The appointment of Senator David Mark as interim national chairman and Ogbeni Rauf Aregbesola as secretary of the ADC raises questions about the coalition’s viability and its potential impact on Tinubu’s administration.

The decision to abandon the newly formed Alliance for Democracy (ADA) and the Social Democratic Party (SDP) in favor of the historically underfunded ADC may seem like a desperate gamble. However, the motivations behind this shift are complex—entwining personal ambitions, intra-party dynamics, and a broader desire to reclaim political relevance. Still, the reality of Nigerian politics suggests this coalition might be more of a mirage than a formidable opposition.

At the heart of this realignment is Atiku Abubakar, a seasoned politician whose ambitions have often been overshadowed by perceptions of greed and betrayal. The view that he has hijacked the movement raises eyebrows and casts doubt on the coalition’s authenticity. In a political landscape where trust is scarce, the motivations of figures like Abubakar are constantly scrutinized. His past dealings with some of the very members now aligning with the ADC only add to the skepticism surrounding the new alliance’s integrity.

Nigeria’s political history is replete with alliances born out of convenience rather than conviction—often fragile and short-lived. Despite its new leadership, the ADC remains a party with limited financial resources and scant presence in Northern Nigeria—a region critical to securing electoral victory. Its weak grassroots structure and lack of deep-pocketed backers raise legitimate concerns about the party’s capacity to challenge a sitting president meaningfully.

Funding is central to any political campaign, and here, the ADC faces a significant hurdle. Speculations that Abubakar Malami, a controversial figure with a checkered past, might bankroll the party come with inherent risks. The shadow of the Economic and Financial Crimes Commission (EFCC) looms large, potentially discouraging any dubious financial inflows. Additionally, former President Olusegun Obasanjo’s past remarks questioning Atiku’s trustworthiness serve as a warning to potential supporters and investors.

On the other side, President Tinubu enjoys the advantages of incumbency—an entrenched party structure and deep financial war chest. The All Progressives Congress (APC) has proven its ability to mobilize resources and national support, a feat that contrasts sharply with the ADC’s precarious situation. The APC’s continued success, historically aided by the popularity and grassroots appeal of Muhammadu Buhari, provides a foundation the ADC currently lacks. Without a unifying, charismatic figure capable of inspiring widespread support, the ADC’s chances appear dim.

Northern Nigeria remains the decisive battleground in presidential elections. It is a region where political allegiances shift, and swing votes determine outcomes. The ADC’s limited recognition in this strategic zone is a significant liability. Its inability to penetrate Northern politics effectively diminishes its electoral prospects.

The recent political isolation of influential figures like Nasir El-Rufai—now aligned with the SDP—further weakens the ADC’s coalition. El-Rufai’s influence and following in the North could have significantly bolstered the party’s credibility. His departure from the fold underscores a broader fragmentation of the opposition, inadvertently consolidating Tinubu’s position.

Perhaps most consequential is the gradual implosion of the PDP, one of Nigeria’s two historically dominant parties. Internal fractures, defections, and the emergence of splinter groups have eroded the PDP’s capacity to act as a unified, credible opposition. Its internal disarray not only jeopardizes its electoral future but also weakens broader opposition efforts against the APC.

This decline is symptomatic of a larger malaise in Nigerian party politics, where the pursuit of power often trumps ideology and cohesion. As the ADC attempts to fill the void left by a splintered PDP, it faces an uphill battle in uniting diverse and often conflicting interests under a coherent agenda.

Given these realities, the 2027 elections may indeed prove to be a political “workover” for President Tinubu. The fragmented opposition, lack of grassroots reach, and financial constraints place the ADC and its allies at a severe disadvantage. Unless a radical and unified strategy emerges, Tinubu’s path to re-election may be far less challenging than anticipated.

Still, the evolving political landscape offers important lessons. While the ambitions of ADC’s new leadership may be laudable, structural limitations remain formidable. As Nigeria gears up for another electoral cycle, political actors must reflect on the imperatives of unity, credibility, and long-term vision.

Ultimately, the 2027 elections may serve as a litmus test for the resilience of Nigeria’s democratic institutions—and for the capacity of its leaders to transcend personal ambition in pursuit of a broader national good.